Economy Classic:

Muscles Galore

Why was production of the MGB V8 dropped after three years of half-hearted production?

Was there behind-the-scenes skulduggery?

Roger Bell remembers, with affection, a tough car.

as published in British V8 Magazine, Volume XVI Issue 1, May 2008

Re-printed unedited by exclusive written permission of "Motor".

This article originally appeared in their issue for the week ending December 18, 1982.

THE TROUBLE with most MG sports cars was that they were too slow. Not even fanatical

loyalists could claim crackerjack performance for the MGB, the most numerous of them

all, when modest saloons of lesser capacity could comfortably outrun it, especially

during the latter half of its long 18 year production life.

The irony of the situation is that MG made three post-war attempts to produce really

quick sports cars, and all three ended in commercial failure The oil-guzzling MGA Twin

Cam (1958-60) was a recalcitrant, fragile machine, easily broken by abuse and poor

petrol. Only 2,111 were made. While it lasted, though, no one could accuse it of being

slow, with 0-60 mph acceleration in 9.1 seconds and a top speed of 115 mph. By late-'Fifties

standards it was a 1600cc fireball.

The same cannot be said of the miserable MGC (1967-69), BMC's meek replacement for the

masculine Austin-Healey 3000. Its gutless and overweight engine denied it the sort of

potency buyers expected of a 3-litre sports car and it was dropped. As an acknowledged

failure right from the start, the "C" did well to reach the 9,000 mark, half of them

fixed head GTs.

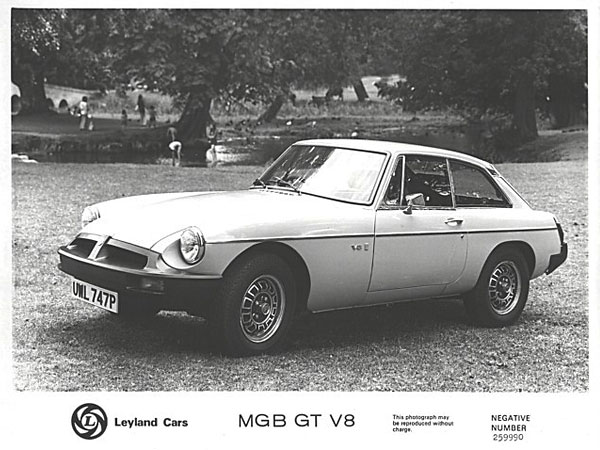

Leyland Cars: MGB GT V8 publicity photo - negative number 259990

It was another three years before MG - now under British Leyland's tangled corporate umbrella tried again with the BV8. Surely this would be third time lucky? Even though the body and chassis were by then a decade old and the engine even older (yes, really), the two in harmony seemed a perfect match. Here, at last was an Abingdon sports car with real performance that its makers could be (and were) proud of, that customers would want, that owners would cherish. It couldn't fail - yet t did! Cynics will say, not without justification, that it was allowed to fail, which is strange considering that the BV8 was arguably the most desirable post-war MG sports car and without question the quickest.

Looking back on it, neither British Leyland nor the Press treated the V8 with the respect

it deserved. Surprisingly lukewarm road tests (Motor's among them) didn't help, but they

weren't the cause of the car's premature demise in 1976, after just over three years of

half-hearted production following a gestation period that was almost as long.

Probing the issue in his excellent book "MG" Wilson McComb quotes former Abingdon chief

John Thornley. "There was a lot of behind-the-scene skullduggery... something about a

limited license to build just so many of that enqine... I don't know why they canned it -

whether they really wanted the engine for some other purpose or whether some stinker

was jealous of it... it really was so good."

So, why was it dropped? Officially, because the dwindling sales (production declined from

1,069 cars in '73 to a mere 176 in '76). The rising cost of fuel in the wake of the energy

crisis, which unfortunately struck just when the V8 was launched, inevitably depressed

demand - but then, the BV8 was not a gas guzzler; its thirst for fuel was in fact quite

modest. Given the right corporate support, the car might well have survived the fuel scare

(as many others with heavier consumptions did) and continued its cut-price supercar role

as Abingdon's flagship even though Type Approval problems prevented its sale in the

all-important US market.

The V8's compact engine sat well back in the monocoque.

There's no doubt that BL did at the time need a healthy supply of the ex-GM Iight alloy

V8 for the Range Rover and SDI 3500, announced in June 1976 a month before the MG was

dropped. But that shortage soon reversed into a glut. As the four cylinder BGT - by now

ludicrously slow compared with modern hot hatches like the Golf GTi - continued for

another four years, until Abingdon's sad closure, the decision to drop the V8 was at best

short sighted.

Jealousy? There's plenty of evidence to indicate that BL's Triumph wing, arch rivals of

MG before and after the Abingdon camp was drawn into the Leyland fold under Sir Donald

(later Lord) Stokes, was favoured in certain corporate decisions at the expense of MG.

For instance, the BGT was withdrawn from the US market to assist TR7 sales there (a decision

that was poorly received by American MG buffs). It is also reasonable to assume that the

projected Rover-engined TR8 (stillborn as it happened) would have had preference over the

much older MGB V8 - and rightly so, as it was a generation younger and generally superior.

Whether it would have been as successful as a US-legal MG, which had enormous untapped

potential, is open to question. MG kudos was a strong marque weapon, as BL are rediscovering

with the runaway success of the Metro quickie, which could well become the best-selling MG

ever. What does seem clear, with the benefit of hindsight, is that the BV8, given the right

support and development, could have done a lot more for its makers than they allowed.

There is a silver lining to this cloudy tale. By dropping the car prematurely, BL did future

owners a good turn by bestowing on the V8 the valued quality of scarcity appeal. Only 2,591

were built. Now, almost a decade on from its launch, the BV8 is one of the very few so-called

modern classics that can seriously be considered not only as a hedge against inflation (if not

a gilt-edged investment) but also a sensible, reasonably-priced slingshot for everyday motoring.

The "plus 2" part of the car was almost non-existent, as shown above,

but it was a civilized two-seater with generous luggage space.

It was the disappointing "C's" failure that paved the way for the MG V8, though the story really starts over a decade earlier with the launch of the MGB in 1962. The MGA's successor, designed at Abingdon under Syd Enever's direction, with a little styling help from Pinin Farina (the name was split in those days), was the first monocoque-bodied MG sports car, providing better accommodation and comfort than the MGA even though it was shorter in wheel base and overall length The capacity of BMC's pushrod ''four", long in the tooth even then, was increased to 1,798cc, bumping up power to 95 bhp and torque to 107 lb.ft. Engine and transmission were strengthened but the rest of the running gear was similar to the "A's" - live cart-sprung rear axle included.

Enjoying this article? Our magazine is funded through the generous support of readers like you!

To contribute to our operating budget, please click here and follow the instructions.

(Suggested contribution is twenty bucks per year. Feel free to give more!)

The ragtop "B" was an instant success and MG production soured. It peaked again after the

launch, in 1965, of the closed GT, one of the cleanest and best-proportioned cars to leave

a British factory in the 'Sixties. Although nearly 2 cwt heavier than the open car, better

penetration gave it a higher top speed (acceleration was little affected). With more weight

over the back wheels, it also handled better. Considered as a civilized two-seater with

generous luggage space it was, by the standards of the day, a marvelous eye-catching package,

living up to its tag of "the poor man's Aston Martin" with real authority.

In 1966 the BGT helped to push MG production to a record 40,000 cars, and BMC as they

then were to the Number Two importer's spot (behind VW) in the States. Heady days! They

were never to be repeated, though, as crash-safety and clean-air legislation, not to

mention the rising tide of imports from the East, then began to erode MG sales.

It was US legislation that finally killed the ailing Austin-Healey 3000 which had no

chance of meeting the new crash-test rules The MGC effectively took its place, which was

a sensible marketing ploy as MG's name abroad was stronger than Austin-Healey's The idea

was right but the product was not. Powered by a long and hefty seven bearing version of

the old pushrod "six" intended for the new big saloon, the "C" was a flop. The Press

crucified it (unfairly, say many keen owners now). "Enthusiasts familiar with the fierce,

masculine behavior of the Austin-Healey 3000 may find the performance disappointing." Motor's

road test went on to criticize the engine's feeble low-speed torque; disagreeable fan whine

(a poor substitute for exhaust growl), unwieldy handling marred by excessive understeer, and

poor seats, among other things. "It is more of a high-speed touring vehicle than a sports car,"

the test concluded, damning the "C" with faint praise. It was certainly no he-man substitute

for the Big Healey which, despite its many faults, was great fun to drive. Sales dipped and

the "C" was dropped in 1969.

The other strand of the story started when Rover acquired the rights from General Motors to

manufacture a particularly neat all-alloy V8 pushrod engine, used by Buick between 1960 and

1963 and rendered redundant by new thin-wall iron casting techniques. Rover was then an

independent company, which is perhaps just as well as they would probably never have got

their V8 otherwise. It first appeared in Rover guise in the stately P5 3.5 litre in 1967 -

the same year that Rover was absorbed by Leyland Motors, the same year as the MGC's launch.

When Leyland merged with British Motor Holdings, as BMC had become, the following year, the

way was theoretically clear for a Rover (nee Buick)-engined MG.

Morgan were the first to demonstrate that the lightweight V8 in a sports car chassis spelt

dynamite. There was plenty of Press speculation at the time about other possible uses for

the Rover enqine, but it was an enterprising specialist, Ken Costello, who first put a V-engined

MGB on the market. The Abingdon people who had experimented with Coventry Climax and Daimler

engines from Jaguar's stable, needed little encouragement from British Leyland's top brass

to do likewise, though it was a couple of years before the BV8 was released for sale, in

the Summer of 1973.

Bob Fisher's MGB GT V8 (bought in Great Britain and brought to U.S.A.)

Specification Comparison

| MGB GT | MGC (roadster) | MGB GT V8 | ||

| SPECIFICATIONS | ||||

| Cylinders | 4 in line | 6 in line | V8 | |

| Bore / stroke, mm | 80.2 x 88.9 | 83.3 x 88.9 | 88.9 x 71.1 | |

| Capacity, cc | 1,798 | 2,912 | 3,528 | |

| Valves | ohv | ohv | ohv | |

| Bhp / rpm | 95 / 5,400 | 145 / 5,520 | 137 / 5,000 | |

| Lb.ft. / rpm | 110 / 3,000 | 170 / 3,500 | 193 / 2,900 | |

| Transmission* | 4-speed + o/d | 4-speed + o/d | 4-speed + o/d | |

| Front Sus. | wishbones, coils | wishbones, tor. bars | wishbones, coils | |

| Rear Sus. | live axle, leafs | live axle, leafs | live axle, leafs | |

| Weight cwt | 20.8 | 22.2 | 21.2 | |

| PERFORMANCE | ||||

| Max speed, mph | 107.6 | 118.2 | 125.3 | |

| 0-60 mph, sec. | 11.6 | 10.0 | 7.7 | |

| 30-50 (4th), sec. | 8.8 | 9.4 | 6.2 | |

| 50-70 (4th), sec. | 13.1 | 11.7 | 6.3 | |

| Overall, mpg | 27.4 | 19.3 | 19.8 | |

| Touring, mpg | 33.0 | 25.6 | 25.7 | |

| Test Year | 1970 | 1967 | 1973 | |

| PRODUCTION | ||||

| Years | 1962-80** | 1967-69 | 1972-76 | |

| Numbers | 513,626 | 8,999 | 2,591 | |

| *as tested by Motor. | **all MGB's. | |||

The V8 was in every way a better car than the MGC. Its compact engine sat well back in the

monocoque, so the "B's" normal wishbone suspension was retained. (the long engine of the

nose-heavy "C" dictated a front-end redesign utilizing torsion bar springs). The 320lb engine

was 40 lb lighter than the all-steel "B's", a whopping 240 lb less than the jumbo sized "C's"

so it didn't upset the car's balance. What's more, its smoothness and output lifted the car

into a new league.

Costello had used the "B" gearbox, stretched beyond the limit by the increased torque. MG

wisely opted for the stronger "C" box and, playing very safe, a low compression (8 25:1)

engine like that used in the Range Rover. With 137 bhp, the GT-only BV8 was actually not

as powerful as the 145 bhp "C", but because it weighed less and developed much more torque

(193 lb ft at 2,900 rpm against the "C's" 170 at 3,500), it was appreciably faster and handled

much better. With the SD1 10.25:1 engine, it would have rivaled the performance of the much

more expensive Jaguar E-Type, still in production when the B was launched. Jaguar might have

been even more displeased by an MG that outran their XJS, launched in September 1975, a year

before the V8 was dropped. (It's encouraging to see that BL's present top brass see things in

a different light, otherwise the new Rover Vitesse might never have happened.)

The first 1,072 V8s made had chrome grilles and bumpers. The rest were rubber-snouted to comply

with US safety regulations. Stiffer rear springs and fatter 175 section tyres carried on

attractive light-alloy wheels made even the early V8s ride a little above the normal BGT. To

avoid the much-criticized bulging bonnet of the "C", a special inlet manifold was devised to

contain the engine under the standard bonnet.

On the road

Motor's testers (and I was one of them) were evidently in two minds about the BV8 when it was

assessed in August 1973. "It really is something of an enigma. Does one regard it as an uprated

MGB or as an entirely new car?" The test report was couched in terms that left the reader in no

doubt that even though the V8 was great to drive it failed to live up to expectations fuelled by

two years' eager anticipation.

At £2,294 it was considered expensive for a car with: a poor ride ("the vintage nature of the

suspension really shows up at low speeds''), dated unmodernized cabin ("the dashboard layout

is rather crude and austere... irritating trivialities outweigh the good points"), inefficient

heater ("antediluvian controls"), and disagreeable wind rush ("at 70 it is noisy... above this

speed makes fast runs a misery"). Not even the performance got a five-star rating, though against

other like-priced rivals it was considered "very respectable".

It was the Ford Capri 3000GT, then costing £1651, that probably tempered Motor's enthusiasm for

the MG. The Ford's top speed of 120 mph and 0-60 mph acceleration of 8.6 seconds were not that

far short of the V8's 125 mph and 7.7 seconds. What's more, the Capri was a full four-seater,

albeit not one then with a hatchback tail. There's no doubt that the MG could have been quicker.

Whether it needed to be is another matter. As Motor observed, "What the bald figures cannot

convey is the utter smoothness, refinement, and lack of drama... and the delightful surge when

accelerating hard. Flexibility is remarkable, and 1,000 rpm in top gear is quite usable in traffic.

Such quotes underscore the BV8's strong suit of effortless speed, it was not a busy flier but

a potent smoothie which tended to throw into prominence deficiencies in other departments, most

of them stemming from the car's age. Remember, the MGB was already nearly 10 years old.

Today the flaws which rightly disappointed Motor's testers when the V8 was new nearly a decade

ago no longer jar. You expect an MG of this vintage to feeI rather dated. You prime yourself

to accept its shortcomings. It was in this frame of mind that I recently drove a '74 BV8 and

was very agreeably surprised. The car belongs to Richard Monk who bought it secondhand in 1976

for £1,900. He values it now at around £3,500 even though it's in largely original condition

(in other words, it hasn't been restored), used as everyday transport and has covered over

100,000 miles without major mechanical overhaul. The engine feels good for another 100,000

miles, highlighting one valued quality that Motor's testers couldn't assess on their low-mileage

demonstrator: longevity. The BV8's lazy, lowly-stressed engine invariably outlives the rather

rust-prone body, though that of Richard's cosetted black car was in exceptional condition.

Treated and resprayed sills had arrested corrosion, but small bubbles at the base of the screen

indicated the need for further attention.

The interior (which looked virtually brand new) didn't feel so stark and dated as anticipated,

and the cloth-covered seats were excellent. I'd forgotten just how comfortable they, and the

relaxed driving position vvere.

Even with the original "agricultural" Range Rover engine, acceleration is strong and clean and

the gearbox (which displayed no overt signs of wilting after eight year's use) had a much

sweeter change than the original test car's. Lever movement was light and precise, no longer

"stiff and notchy" as Motor had described it in 1973. In fact the whole of the drive-train

felt and sounded in excellent shape, with no sizzle, vibration or clonks to betray wear.

I was also impressed with the car's roadholding and handling, even allowing for the 185-section

tyres (one size up on standard) fitted by Richard Monk. It clung on well, felt reasonably agile

(unlike the unwieldy "C") and neither scrubbed its front tyres with excessive understeer nor

side-slipped its rear ones under provocative power. The car's balance and neutrality made it

feel very reassuring.

Not even the firm ride seemed quite so harsh as Motor's test had suggested, maybe because of

the different tyres and non-standard telescopic dampers I could tolerate the crude suspension

more readily then the awful wind noise which completely drowned the smooth, satisfying burble

of the engine except at low speed. If a sports car is going to be noisy - and this one is -

it's got to make the right sort of noise. The tearing, buffeting, whooshing cacophony created

by the V8's pillars and window frames (and aggravated on this car by a sunshine roof) is an

objectionable racket. Pity.

If you can accept this and other shortcomings, a BV8 still makes a lot of sense as a fast

and practical two-seater express. Modern counterparts are likely to set you back three or

four times as much, and depreciate much faster - even cars like the Porsche 944 (£13,390),

TVR Tasmin Fixedhead (£13,824), and Lotus Eclat Excel (£13,787). The highly acclaimed

Capri 2.8i (£8,125) could barely keep in, which underlines just how quick the V8 was in its

day - and still is now.

Richard Monk asserts that running costs are remarkably low. He reckons to get 30 mpg on a

long run, driving with restraint, 24-25 mpg in town. Thrash the car hard, though, and you'd

be lucky to get 18-20 mpg. Although the V8 is in Group 7, fully comprehensive insurance for

a good-risk driver over 25 years old can be arranged through the MGOC for around £150.

Buying a BV8

Prices range from £1,700 (scruffy) to over £5,000 (concours). The early chrome-fronted cars

are more highly prized than the subsequent rubber-bumpered ones though expect to pay more

for a late, low-mileage R-registered model than an early L-registered one. In the end,

though, condition rather than age is what really matters.

Bodywork is the same as the BGT's, so look for rust in the usual places - sills, rear wheel

arches and front wings. Repair sections (as opposed to complete body panels) are available

through the clubs, so corrosion need not be a killer.

Engines are long-lived (police pursuit BV8s ran for 130,000 miles between overhauls) but

the hydraulic tappets are likely to become clattery after 60,000 miles. They're fairly easy

to replace, but remember that there are 16 of them at around £6 each. Overheating can cause

serious gasket and head-warping trouble but it's very rare, even though the automatic twin

electric fans are prone to seizure, especially after Winter when they rarely come into play.

Early '73 cars did suffer from gearbox trouble before the internals were beefed up. After

that, the transmission was not an inherent weakness unless punished. If the overdrive

(fitted on third and top on early cars, top only on later ones) plays up, it's probably

caused by the usual solenoid trouble.

Life expectancy of the lever-arm dampers, like those of the "B", is about 18 months. Spax

telescopic ones (as fitted to Richard Monk's car) are a popular swap as they last longer

and improve the ride and handling. Wider 185-section tyres, stainless steel exhausts (the

standard mild-steel ones go in a year), electronic ignition and shorter springs for the

jacked-up rubber bumpered cars are also accepted modifications.

Spares are generally readily available through the clubs, notable exceptions being the

chromed alloy wheels (which corrode) and the special rear axle.

When Motor published this article, they illustrated it with eight photos of an early

("chrome bumper") MGB GT V8 bearing license plate "HOH 933L". Unfortunately, our copies

of these photos aren't suitable for reproduction. We've substituted one Leyland Cars

publicity photo plus photos from the personal collections of British V8 readers Bob Fisher

and Jake Voelckers respectively. We're delighted to show off some handsome later-model

('75 and '76 "rubber bumper") MGB GT V8's.

BritishV8 Magazine has assembled the largest, most authoritative collection of MG "MGB GT V8" information you'll find anywhere. Check it out! Access our MGB GT V8 article index by clicking here.