Oldsmobile "215" Stroker Motor (289 cid) - Part 1

By: Kurt Schley(This article appeared in Volume XI Issue 3, September 2003.)

Long-time readers of the Newsletter may remember that several times over the last five years or so, I have claimed that I was on the threshold of an MGA V8 project. Due to a combination of increased hours required at my job, a home relocation, assisting my father in building and moving into a new home (400 feet behind mine) and other factors the MGA shell and chassis have been sitting untouched and forlorn. However, circumstances have finally combined to allow the project's initiation. First on the agenda will be building the MGA's engine, as it will temporarily replace the worn out Olds 215 in my '74 MGB. After a season's tuning and break in, the new engine will be pulled and stored until the "A" is ready.

I had originally planned a stock displacement Olds 215 with longer connecting rods, i.e. Buick 300.

There are several advantages to a long-rod engine. I had collected most of the components for this

engine when fate intervened in the form of a phone call from Dan LaGrou at D&D Fabrications.

Dan had purchased an Olds stroker motor and had everything except the heads available. It seems that

the engine was originally built many years ago to power a racing hydroplane boat (for which the 215

engine was a popular mill). The engine was apparently built, run on a test stand or a dyno only once

for a short period of time, never installed into the hydroplane, and stored. Eventually the boat and

engine's owner passed away and the combination was purchased by a fellow in Arizona. The new owner

had no plans to use the aluminum V8 and contacted Dan. When the motor eventually made it to the

D&D shop in Michigan, it was pretty much an unknown entity. The heads were found to have been

extensively ported and were soon shipped off to one of Dan's customer's, leaving the balance of the

engine on the engine stand.

When the heads and oil pans were removed, the long block turned out to be a treasure trove of mid-sixties Mickey Thompson speed parts. A 3-3/4" welded crank (yielding 289 cubic inches), boxed connecting rods, M/T pistons, roller cam and roller lifters, reinforced cam gears, and a block machined for the crank and rod clearances. The main bearing caps are reinforced with massive steel supports about an inch thick. The pistons show just a hint of heat tint, evidence of only a few minutes running time.

Over the next few months, I will be going over each component of the engine, measuring, cleaning and improving where feasible. For instance, the roller cam is an unknown. I will have to have it "mapped" by a cam expert to figure out the specs and whether it is suitable for street use. The progress of this project will be documented for the Newsletter (Actually, I have mixed emotions about even using all these neat vintage parts in a running motor, due to their rarity. They would look great on the fireplace mantle!).

Being that the engine came to me with no heads, I decided this would be the first problem to be addressed. The Buick/Olds 215, as well as the Rover, V8's, are well known to be head restricted. That means the port size/configuration and the rather smallish valve diameters will not allow sufficient fuel/air flow to make real power. Even mild porting, while entirely worthwhile, will not allow the engine to breath enough to reach full potential. I could have used modified later Rover heads, but this would have created problems with the valve train and with compression. The pistons/compression ratio were set up for the 51cc (casting suffix -746) low-compression Olds heads. Using Buick/Rover heads with their 37cc chambers, would have resulted in a compression ration in excess of 11.5:1. So, the heads would have to remain Olds 215, but would require extensive reworking in order to support 289" cid. One favorable factor is that the long stroke will dictate a rather low maximum RPM, somewhat lessening the flow requirements for the heads.

When the heads and oil pans were removed, the long block turned out to be a treasure trove of mid-sixties Mickey Thompson speed parts. A 3-3/4" welded crank (yielding 289 cubic inches), boxed connecting rods, M/T pistons, roller cam and roller lifters, reinforced cam gears, and a block machined for the crank and rod clearances. The main bearing caps are reinforced with massive steel supports about an inch thick. The pistons show just a hint of heat tint, evidence of only a few minutes running time.

Over the next few months, I will be going over each component of the engine, measuring, cleaning and improving where feasible. For instance, the roller cam is an unknown. I will have to have it "mapped" by a cam expert to figure out the specs and whether it is suitable for street use. The progress of this project will be documented for the Newsletter (Actually, I have mixed emotions about even using all these neat vintage parts in a running motor, due to their rarity. They would look great on the fireplace mantle!).

|

Enjoying this article? Our magazine is funded through the generous support of readers like you! To contribute to our operating budget, please click here and follow the instructions. (Suggested contribution is twenty bucks per year. Feel free to give more!) |

Being that the engine came to me with no heads, I decided this would be the first problem to be addressed. The Buick/Olds 215, as well as the Rover, V8's, are well known to be head restricted. That means the port size/configuration and the rather smallish valve diameters will not allow sufficient fuel/air flow to make real power. Even mild porting, while entirely worthwhile, will not allow the engine to breath enough to reach full potential. I could have used modified later Rover heads, but this would have created problems with the valve train and with compression. The pistons/compression ratio were set up for the 51cc (casting suffix -746) low-compression Olds heads. Using Buick/Rover heads with their 37cc chambers, would have resulted in a compression ration in excess of 11.5:1. So, the heads would have to remain Olds 215, but would require extensive reworking in order to support 289" cid. One favorable factor is that the long stroke will dictate a rather low maximum RPM, somewhat lessening the flow requirements for the heads.

Participants of the past MG V8 Conventions know Dale Spooner. Dale has been a V8'er for many years

and one of the first builders to have put together a well handling Ford 302 small block MGB. In

addition, Dale is the proprietor of one of New England's premier engine machine shops, Motion

Machine in South Burlington, VT. Motion Machine specializes in the precision machining required for

successful high performance and exotic engine building. Many other machine shops routinely send their

difficult work over to Dale, such as four valve/cylinder heads, Ferrari and other exotics, as well as

rectification of other's bungled jobs. For high performance head work, Dale works closely with Dwayne

Porter, a master porting and high performance head expert. Dwayne has his flow bench and porting

equipment in the Motion Machine facilities.

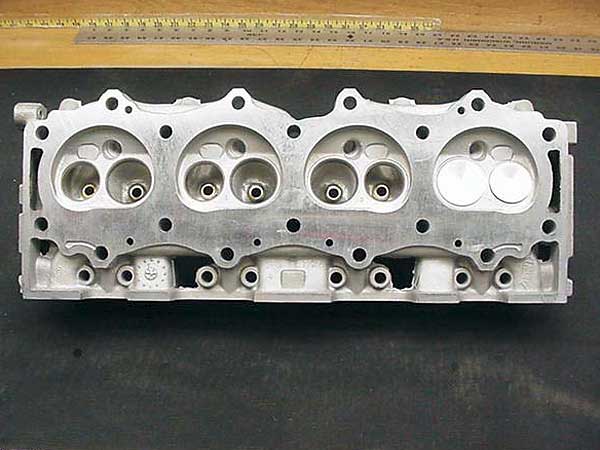

In conversations with Dale, it was decided to send a set of Olds heads up to him, so that he and Dwayne could decide how best to make the heads flow to their full potential. I also sent a scrap head for experimental work. A few weeks later, the revamped heads arrived back and they are gorgeous, suitable for display on the living room coffee table! Through extensive machining, component selection and porting, the heads are now capable of flowing enough air/fuel to keep the stroker well supplied. The components are listed below:

• Intake Valves - Ferrea Racing Components p/n F6223 (Ford 2.3L) 1.74" head diameter, 11/32" diameter stem, 4.800" overall length, 0.400" tip length

• Exhaust Valves - Ferrea Racing Components p/n F6224 (Ford 2.3L) 1.500" head diameter 11/32" diameter stem, 4.800" overall length 0.400" tip length

• Valve Springs - Competition Cams p/n COM-901-16 (outer spring with damper) 1.500" O.D. 1.080" I.D. 110 lb at 1.650" load at checking height, 290 lb@1.150" load at open height, 1.110 coil bind height

• Spring Retainers - Competition Cams p/n COM-743-16, steel (Chevy-Olds-Pontiac-SB Ford) 7 lock angle

In conversations with Dale, it was decided to send a set of Olds heads up to him, so that he and Dwayne could decide how best to make the heads flow to their full potential. I also sent a scrap head for experimental work. A few weeks later, the revamped heads arrived back and they are gorgeous, suitable for display on the living room coffee table! Through extensive machining, component selection and porting, the heads are now capable of flowing enough air/fuel to keep the stroker well supplied. The components are listed below:

• Intake Valves - Ferrea Racing Components p/n F6223 (Ford 2.3L) 1.74" head diameter, 11/32" diameter stem, 4.800" overall length, 0.400" tip length

• Exhaust Valves - Ferrea Racing Components p/n F6224 (Ford 2.3L) 1.500" head diameter 11/32" diameter stem, 4.800" overall length 0.400" tip length

• Valve Springs - Competition Cams p/n COM-901-16 (outer spring with damper) 1.500" O.D. 1.080" I.D. 110 lb at 1.650" load at checking height, 290 lb@1.150" load at open height, 1.110 coil bind height

• Spring Retainers - Competition Cams p/n COM-743-16, steel (Chevy-Olds-Pontiac-SB Ford) 7 lock angle

Dwayne performed a baseline flow-bench test of the stock Olds head with stock valves. He then proceeded

to develop the optimal port shape and size, performing three additional flow bench tests at various

stages of the development.

• Test 1 - Stock Oldsmobile 8.75:1 aluminum head with stock 1.525" diameter intake valves and 1.350" diameter exhaust valves.

• Test 2 - Basic full port job, intake opened to 1.70" x 1.00", stock valves, 30 back cut on the valves, competition valve job.

• Test 3 - Basic full port job, intake opened to 1.70" x 1.00", 1.620" diameter intake valve, 1.400" diameter exhaust valve, both valves with 30 back cut, re-blended bowls.

• Test 4 - Basic full port job, intake opening to 1.80" x 1.00", 1.620" diameter intake valve, 1.400" diameter exhaust valve, both valves with 30 back cut, re-blended bowls, fully polished runners, more guide streamlining.

The final results showed an approximate 32 percent increase in intake flow and a whopping 54 percent in the exhaust flow (both at 0.600" lift).

Disclaimer: This page was researched and written by Kurt Schley. Views expressed are those of the author, and are provided without warrantee or guarantee. Apply at your own risk.

• Test 1 - Stock Oldsmobile 8.75:1 aluminum head with stock 1.525" diameter intake valves and 1.350" diameter exhaust valves.

• Test 2 - Basic full port job, intake opened to 1.70" x 1.00", stock valves, 30 back cut on the valves, competition valve job.

• Test 3 - Basic full port job, intake opened to 1.70" x 1.00", 1.620" diameter intake valve, 1.400" diameter exhaust valve, both valves with 30 back cut, re-blended bowls.

• Test 4 - Basic full port job, intake opening to 1.80" x 1.00", 1.620" diameter intake valve, 1.400" diameter exhaust valve, both valves with 30 back cut, re-blended bowls, fully polished runners, more guide streamlining.

The final results showed an approximate 32 percent increase in intake flow and a whopping 54 percent in the exhaust flow (both at 0.600" lift).

| EXHAUST - Tests corrected for 28" H2O | ||||||||

| Lift | Test 1 | Test 2 | Test 3 | Test 4 | ||||

| % | CFM | % | CFM | % | CFM | % | CFM | |

| 0.100 | 69 | 835 | 71 | 36 | 90 | 45 | 91 | 46 |

| 0.150 | 75 | 52 | 80 | 55 | 93 | 64 | 92 | 64 |

| 0.200 | 64 | 65 | 71 | 73 | 75 | 76 | 77 | 78 |

| 0.250 | 72 | 73 | 84 | 85 | 86 | 88 | 88 | 90 |

| 0.300 | 76 | 77 | 94 | 96 | 97 | 99 | 99 | 101 |

| 0.350 | 78 | 80 | 72 | 105 | 75 | 108 | 77 | 112 |

| 0.400 | 80 | 81 | 76 | 110 | 79 | 114 | 81 | 118 |

| 0.450 | 58 | 84 | 79 | 114 | 82 | 119 | 85 | 123 |

| 0.500 | 58 | 84 | 82 | 119 | 85 | 124 | 87 | 126 |

| 0.550 | 58 | 84 | 83 | 120 | 87 | 126 | 89 | 129 |

| 0.600 | 58 | 84 | 84 | 122 | 88 | 127 | 90 | 130 |

| INTAKE - Tests corrected for 28" H2O | ||||||||

| Lift | Test 1 | Test 2 | Test 3 | Test 4 | ||||

| % | CFM | % | CFM | % | CFM | % | CFM | |

| 0.100 | 63 | 43 | 69 | 48 | 74 | 51 | 74 | 51 |

| 0.150 | 62 | 63 | 70 | 72 | 76 | 77 | 76 | 77 |

| 0.200 | 84 | 85 | 66 | 95 | 72 | 104 | 72 | 104 |

| 0.250 | 72 | 104 | 76 | 111 | 88 | 128 | 88 | 128 |

| 0.300 | 80 | 116 | 85 | 124 | 81 | 146 | 81 | 147 |

| 0.350 | 84 | 122 | 95 | 138 | 88 | 159 | 89 | 161 |

| 0.400 | 71 | 128 | 83 | 150 | 93 | 168 | 95 | 172 |

| 0.450 | 73 | 133 | 87 | 158 | 93 | 168 | 95 | 173 |

| 0.500 | 74 | 134 | 91 | 165 | 94 | 170 | 96 | 174 |

| 0.550 | 75 | 136 | 93 | 168 | 95 | 173 | 97 | 176 |

| 0.600 | 75 | 136 | 93 | 168 | 95 | 174 | 98 | 178 |

Disclaimer: This page was researched and written by Kurt Schley. Views expressed are those of the author, and are provided without warrantee or guarantee. Apply at your own risk.